Jirel of Joiry

By C. L. Moore

I really love the cover to this book. Unfortunately, the contents are not nearly as good.

C. L. Moore, Catherine Moore, is not a well known author today, perhaps fading into some obscurity if it were not for some keeping knowledge of the "Golden Age" of Science Fiction alive (a period that started in the 1930's). I recently watched a YouTube talk by Jeet Heer where he talked about The Best of C. L. Moore, which he liked, and that encouraged me to pick this up. These are old stories, first published in Weird Tales magazine, the most famous American pulp. The first story in Jirel of Joiry is "Black God's Kiss" from 1934.

I had to push myself through the first, then the second story here. I reminded myself that I originally found Jack Vance's Tales of the Dying Earth hard going because it seemed "pulpy" and written in quite a "basic" style. But by the end of the first book it had found its footing and I was enjoying it a lot. "Jirel" didn't get better for me though and did not seem to improve. I found it dull and repetitive. Too many descriptions of landscapes and feelings that got a bit boring and turgid after a while. I groaned when I hit the word "skyey". From Black God's Shadow :

A cloud floated across its face, writhed for an instant as if in some skyey agony then puffed into a mist and vanished, leaving the green face clear again.

Jirel is a bit of a female Conan and that should be interesting, but there is almost no fighting or sword play, excitement or world building, let alone character. She gets emotional, with lots of anger, hate, love - but that's about it. I don't often drop a book I'm reading but I gave it up after three stories and decided to move on to something better. I have a big pile of books to read, supposedly good ones. I will give Moore another chance in the future: either Doomsday Morning or Northwest of Earth.

Crumb, A Cartoonist's Life

By Dan Nadel

This is a very recently published book I found in my local library: a biography of the American cartoonist Robert Crumb. He's someone I have had mixed feelings about for a long time but, irrespective of that, I also always recognised him as excellent cartoonist. A natural talent, but also the fruit of many years drawing in his younger days, as this book shows.

I first came across Crumb in a book called "Masters of Comic Book Art", a "coffee table" book published by Aurum Press in 1978. Not a great book looking at it today, but in 1978 it was a revelation to a 12 year old boy. But Crumb was not one of the artists I paid as much attention to. He was too "cartoony" for my taste and I was drawn to the Moebius, Druillet and, particularly, Richard Corben chapters.

But chasing the early work of Corben meant exposure to the world of American "underground" comics and I could not avoid the work of Robert Crumb. He was everywhere, very prolific and the core of Zap Comix, the first "real" underground comic book which debuted in 1968. Alongside fellow artists Rick Griffin, S. Clay Wilson, Spain Rodriguez and Victor Moscoso, his work defined the free-wheeling, wild and often quite "obscene" new counter-cultural comics. Crumb was the driving force of Zap and became famous over the next few years. Of course, "obscenity" is a matter of opinion really but there were serious legal and official attacks on some of the work produced and those who drew, published or distributed the work. First Amendment be damned.

Crumb is also well known for creating some very sexist and racist work on occasion and these pieces are hard to look at today. He's a product of a much more sexist and patriarchal society, and racism was something that was much more casually present than today. Crumb is frank about these works and his various sexual and psychological hang-ups, telling Dan Nadel right at the start that he wants no sugar-coating. Nadel details how badly he sometimes treated the women (particularly) in his life: he was quite the philanderer. It shouldn't come as a great surprise, but a lot of the "hippies" enjoying the drugs and "free love" were the same products of such a society and would happily leave the washing up to the women. Crumb interrogates himself painfully in his note books and letters over his multitude of failings, well aware of the hurt he causes. His very dysfunctional family background must have contributed to this.

For a look at him and, particularly, the relationship with his older brother Charles, see Terry Zwigoff's film Crumb. Charles Crumb, committed suicide in 1992.

Dan Nadel's book is well worth a read and not only for the Robert Crumb story but also a glimpse of all the other underground artists he inspired or worked with. In addition, it's a story of the unfolding of the 1960's "counter-culture", especially what was happening at its epicenter in San Francisco. But this was something that reverberated across the whole of the USA, and Europe as well. Music (Crumb meets Janis Joplin), drugs (lots of LSD taken and pot smoked) and general craziness. Like all these things, the scene dissipated quite quickly with many more undesirable sorts moving in and causing trouble. But the story is fascinating, as is this book.

Crumb is now 82 years old (as of December 2025). Is he still working? Has he mellowed at all? Well, he is still working although his published output has slowed significantly. As for mellowing, he has just had a new comic published by Fantagraphics called Tales of Paranoia and he still seems to be railing against much of the horrible reality of the modern world. Including things like surveillance, vaccine mandates and no doubt much else. He is still Robert Crumb, the famous curmudgeonly comic artist after all.

Mythago Wood

By Robert Holdstock

Holdstock's fantasy novel made a big splash back in the 1980's and won some awards. One of the reasons, as mentioned to me in my local SF bookshop, might have been its break with the Tolkien "template" which had been dominating the genre for years.

A "mythago" is a mythic image: something created from the mind of a human being and formed in the real world. They are real bodily things, as real as you or I and can be loved or fall in love, be killed or kill. They might not be human. The created things sprout from myth or history and have a deep, timeless resonance to their source, whether our own unconscious mind or the place itself.

Ryhope Wood seems to have a "supernatural" capability of producing these figures. Inside the ancient wood, we cross one or more thresholds and the normal reality of time and space is broken. A whole world exists separately from ours, peopled by ancient inhabitants and within ancient landscapes.

We meet two brothers, sons of a father obsessed with exploring the wood, living in a house on its edge. When the father dies, each son experiences the draw of the forest and its mysteries. This is also a love story, a chase and a quest. A "created" creature of the wood is Guiwenneth, a young woman with a past steeped in old myth and a pre-Christian world. She is the crux of the novel and the reason for the chase into the further reaches of the forest. Guiwenneth seems to be an avatar of a Celtic warrior princess but also a mythic female figure from long before the Celts appeared. Is there a Jungian collective unconscious? Holdstock explores aspects of this to bring this world to life.

Mythago Wood is a well written adventure book but infused with an exploration of history and myth. This dive through the sights and smells of ancient places and people is the core and what makes it special. It is rooted in the old landscape of an old country, one that has seen many new peoples bringing many new tales. I liked it so much because of that. The novel ends at a point where there is obviously more to say: the sequel is Lavondyss, which I am looking forward to reading.

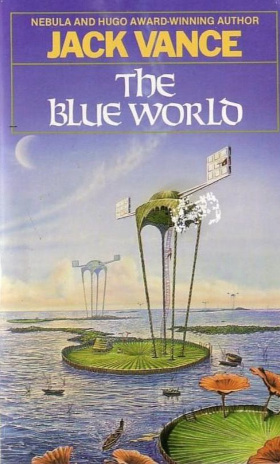

The Blue World

By Jack Vance

An old Jack Vance novel (published in 1966) and another I enjoyed immensely. Nothing taxing about this, just a thoroughly good adventure set on a water world with humans battling monsters.

Here, the "monsters" are gigantic fish-like creatures with big appetites. They call these things "Kragens" and the largest and most troublesome they call "King Kragen". Over the years, they have been placating the "King" so that it keeps other, smaller creatures away. They do this by by feeding it: this has helped it grow to an enormous size and gives them even more trouble because of that.

The people here are the descendants of survivors from a spaceship that crashed a few hundred years before. In what seems to be typical Vance humour, there are various "castes" with names like: the Bezzlers, the Anarchists, the Swindlers. We also have the Advertisermen (yes) and many others. Perhaps survivors of some sort of banishment or perhaps prison (consider the founding of Australia). The descendants of rebels then, they have managed to build a working civilisation from bare bones on a planet devoid of solid ground, rock or metal. Spread out on the ocean over dozens of floating islands, the top-most pads of vast tree-like plants, they survive and thrive - except for the problem with the predators. Some among them are sick of this and are prepared to do something about it.

I like Vance's conciseness and the directness of his prose. It is a pleasure to read. There is no padding but this means little world building. What we learn is intriguing, such as the surviving but fragmentary diaries and documents of the "first" people, but this is not gone into deeply. In addition, I like the characterisation but this too is superficial. However, having said all this, it is a short book and gets to the point; in that sense it is very refreshing (considering the "door stopper" books published nowadays). A caveat I would mention though: it ends quite quickly. I would have liked for it to be extended a bit: indeed, maybe even padded a little.

Jack Vance is an author I wish I'd discovered years ago, especially in my teenage years. I will certainly be reading more.

Me only cruel immortality consumes

-- from the poem Tithonus by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

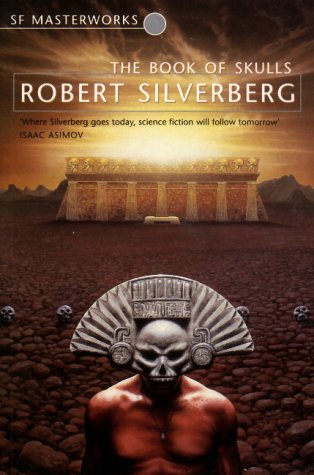

The Book of Skulls

By Robert Silverberg

When I glanced up at my neighbour's door a couple of weeks ago, I saw a small skeleton hanging on a string with an over-sized grinning skull in a faintly "Mexican" style. It was Halloween. Then I thought of the book I was reading, Robert Silverberg's "The Book of Skulls". An apt book for this time of year.

Here we have a road-trip from New York to Arizona with four young men, college room mates, chasing the possibility of eternal life. One of the young men, Eli, found an obscure manuscript in the bowels of a university library and managed to translate some of its message: could it be a promise of immortality? Also, there seems to be a catch.

The four are mismatched and quite different: we have the New York Jew (Eli), clever but not confident; Oliver, the middle American country boy, driven to learn but scared of death; Ned, a homosexual who enjoys taking both or all sides in a perverse way; and Timothy, the east coast American rich boy, born to wealth, with a stand-offish outlook to the whole trip. Silverberg structures the narrative such that each of them takes a turn to speak their mind to us. And so we learn about them: of their various backgrounds, neuroses and loves. The close proximity during the journey leads to friction, resignation, dread and lust (and book has plenty of lust and sex). There is a weight on everyone as the journey progresses; a weight that gets heavier. The reader also starts feeling this; a dread of expectation which ratchets up when the destination is reached.

Although the novel is published here in the Gollancz "SF Masterworks" series, it is not science-fiction, and I would struggle to label it "fantasy". Like the old Memento Mori works of old, Silverberg meditates on death through the eyes of his four young student protagonists. The search for immortality is something with a long pedigree, and a fantastic one at that.

This novel was "easy" to read in so far as it is written well. The multiple narratives split the text up into short chunks. However, I also found it a "tough" read, possibly also due to being in each person's head in turn and starting to feel unsettled about where we were going with the story. You have to think about what it might mean to achieve this goal. At one point, Eli starts to consider all the things he will do if he gains immortality: twenty years of fitness training, twenty years of learning an instrument etc. In a hundred years or so, surely we will be on the Moon or Mars, so getting off Earth. It quickly becomes apparent how long eternity actually is. Do we want that? I do not think any human being is ready for immortality. An unsettling novel.

As for Tithonus :

From Google :

Tithonus was a Trojan prince in Greek mythology who was granted immortality but not eternal youth by Eos, the goddess of dawn, whom he loved. As a result, he continued to age indefinitely, eventually becoming a weakened, shriveled being whom Eos eventually transformed into a cicada out of pity.

From Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem Tithonus :

The woods decay, the woods decay and fall,

The vapours weep their burthen to the ground,

Man comes and tills the field and lies beneath,

And after many a summer dies the swan.

Me only cruel immortality

Consumes: I wither slowly in thine arms,

Here at the quiet limit of the world,

A white-hair'd shadow roaming like a dream

The ever-silent spaces of the East,

Far-folded mists, and gleaming halls of morn.

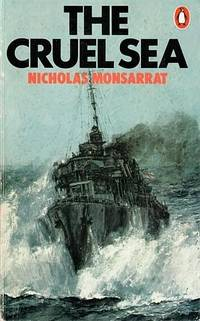

The Cruel Sea

By Nicholas Monsarrat

Monsarrat's most famous novel was published in 1951 and would have been written while his own experience in the war was fresh, and probably raw. It is now seen as a classic and I understand why.

The author served on a naval escort in the North Atlantic during the Second World War, so has direct personal experience of the rigors he writes about. He forges a realistic, exciting and horrifying account of life on a warship. Things got very bad for Britain in the war until they finally started getting better.

It is very humbling to read of the terrible conditions, the suffering, tension and horror the men on these ships had to put up with. Pulled together from all across the world (British, Australian, Canadian etc.) and from all sorts of unlikely professions, they are dropped into a new world of conflict: war with the enemy, with the sea and with the elements. The worst of the ocean weather appears almost unbearable and, on top of this, the constant tension and terror of an unseen enemy, the hated U-Boat, picking off ships of the convoy by day and by night. The torpedoing and its aftermath will stay with me.

This book is grim in parts, but also very funny on occasion, especially the rest and re-fitting stop in New York. The crew discover that the Americans are just like us .. except when they aren't. A great novel of war and how people cope with it.

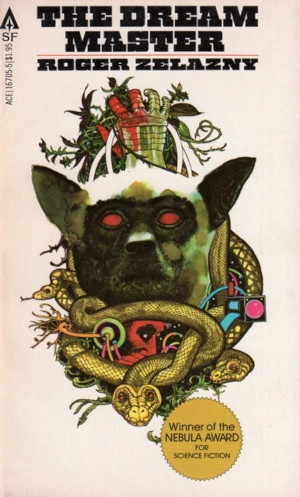

The Dream Master

By Roger Zelazny

When you read a book with "dream" in the title, you have to be prepared for some strange stuff and you'll find that in this short novel by the science-fiction author Roger Zelazny. This is my first time reading him.

In The Dream Master, Charles Render is a therapist who works by participating in his patients' dreams, controlling them in order to find the source of problems they have. He does this using a machine, a technological interface between himself and his subject. He is an expert at this sort of treatment but much care is required due to the risks of being so closely entwined at such a low-level of consciousness. Zelazny uses the process to explore aspects of our emotional and psychological state, neurosis and mental condition. Perhaps also the danger of over-confidence. There's potential for some imaginative sequences which he does well.

As I say, this is a short book and one I found hard to understand in a few places. Things were not necessarily clarified but it was clear that some scenes unfolded inside a dream world somewhere. What was actually happening, and why, was not easy to fathom. Such is the nature of the dream world but it can be frustrating in a novel. Zelazny seems to be an intelligent and cultured writer, making many references to classical or mythological themes, as well as themes of the unconscious. Clever stuff but you need to see the references he makes and, at times, perhaps he is too clever. The conclusion is not a great surprise but handled well. A certain sense of dread.

I am considering having a look at the novella the book is based on: He Who Shapes.

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (a very good and intelligent resource) has a useful paragraph on The Dream Master in its

main article about Zelazny :

"In The Dream Master – for one of the few times in his career – Zelazny

presented the counter-myth, the story of the metamorphosis which fails, the

Transcendence which collapses back into the mortal world."

Tales of the Dying Earth

By Jack Vance

Having read my first Jack Vance book (it was about time), I see why people love the way he builds up a rogues' gallery cast of characters: rogues, cads and misanthropes of all shapes and sizes. Not all human and definitely not necessarily likeable. Cugel takes the center stage for two of the four books and he is a real chancer: untrustworthy and scheming. He did one or two quite horrible things to other people early on but seemed to mellow slightly as things went on. He certainly had much reason to be unhappy given his circumstances.

I had a lot of fun reading the four books that make up Tales of the Dying Earth, although it took me some time to get used to the world and style. The first book was published in 1950 and it betrayed an early "pulp" style that, whilst enjoyable enough in a basic way, can become a bit tiring. However, things improved quickly, including the prose. It was entertaining, often humorous and even moving. You get hooked.

Set on a very far future Earth (millions of years away), our planet is portrayed as being in its last stages: the sun large, red, and failing. With the passing aeons, many changes have occurred and this is nothing like the Earth we know. One major difference is the existence of magic alongside wizards who exercise this skill. It is certainly dangerous to cross a wizard; and Vance brings some wonderfully realised, but sometimes atrociously behaved wizards to life. They are just one of a large number of odd characters we meet: human, monstrous, demonic and all sorts of other-worldly things. Time itself, and the dimensions of space, do not appear fixed things either. The prose is baroque and beautiful, sometimes using old-fashioned or even newly created words to set a style or feeling. He has a huge and fantastic imagination, a wonder to read and one I've rarely encountered (if ever). It is clear why he has been so inspiring to so many. Quite magical in more ways than one.

I'd love to have these books in hardback, as an omnibus or separately. Unfortunately, I don't think that exists or what does exist is expensive. I was in a large local chain bookshop at the weekend and they had no Vance at all. Also no Vinge. A whole bookcase of something called "Romantasy" though, for which I am not the market. Sad. I assume Vance just doesn't get much of a showing on BookTok.

The Circle

By Dave Eggers

The Circle follows the career of Mae Holland, who joins the eponymous company after a few strings are pulled by a college friend Annie. Annie has risen through the ranks and is now highly placed. The Circle is a large and powerful Big-Tech company, getting even bigger and pushing its technology and vision ever further through society, on a global scale. This book was published over ten years ago but is still relevant today, especially as the use of "AI" grows.

There is no longer any anonymity on the internet because Circle's "TruYou" system has taken over identity management and it is required for almost everything now. People know who does what, so bad online behaviour has vanished. And more, their consumer and business marketing and advertising program is just about essential to do any commerce on the internet. Combined with the reach of a massive social media platform ("zings", "smiles" and "frowns" fly about in the ether), the company's reach is planet wide. This means the Circle has huge amounts of data available to its people and algorithms. Even more: small cameras that can be placed anywhere easily, broadcasting 24/7. You can easily look up the quality of the waves at the beach you like to surf from. There is also a project to record and broadcast all your life interactions through a camera around your neck: being "transparent". In the name of democracy, politicians are encouraged to take the brave step of going transparent and the numbers taking part are rising.

As you see, this is Big Tech on steroids.

A cursory read and understanding of the above will make you think of a lot of downsides to this new world order. Eggers mostly leaves the dystopian and darker aspects in the background but does show the terrible consequences for some. It is approaching a panopticon, total surveillance of the sort envisaged for a prison by Jeremy Bentham in the 18th Century. There is little or no discussion of the firm's finances or investors, but we do know there was an IPO, so there will be shareholders. There is a lot of power being wielded, by who? It is left unsaid. Similarly, the acquiescence of sovereign government, domestic and foreign, is not mentioned, other than brief mentions of something like "trouble" in Washington or the EU.

But the juggernaut rolls on; the direction of travel is clear in the world of The Circle. Something very noticeable (apart from some of the speech patterns, see below) was Eggers' portrayal of how enthusiastic and willing the thousands of employees of the company are as they march the world towards a technocratic and dictatorial Final State of complete surveillance. Holland accepts and eagerly rationalises what to most would be an appalling and nightmarish situation: both the result of the technological revolution and the, almost comical, workplace gyrations. Independence of thought is not encouraged, and seems to be easily internalised by the worker bees. I found this difficult to believe. But groupthink does exist and social pressure to "be kind" (cf cancel culture recently) is something to be worried about.

Luckily, so far, there is no one person, company or government fully in charge. But if desires of both an industry and a government do converge, the danger signs should start flashing very brightly.

It's a readable book and a warning about what sort of world we're hurtling towards. I found it hard to believe so many clever people would go along with such an all-encompassing world plan though and some characters were built up to be a stereotype. The potential of "AI" to reduce even further our scope for privacy and human creativity makes the warning more critical today.

Regarding the writing style. I have a quibble about it because it badly jars sometimes. Rather than say "yes" or "no" to answer questions, the people here say things like "I am", or "It is" e.g. "Does that make sense?", "It does" (page 146). They do this all the time, to straightforward questions we would answer naturally with a yes or no. To me, this is highly affected and unnatural speech. I noticed this, but on a much smaller scale, when reading The Expanse series but it is much worse here.

Asterios Polyp

By David Mazzucchelli

This is a graphic novel published in 2009 by David Mazzucchelli, a comic artist acclaimed for his art on Frank Miller's 1987 re-telling of Batman's origin, Batman Year One. He is not a prolific artist but his work has been very influential in the field of comics and graphic novels; seen as a benchmark in the more mature themed and designed work that came of age in the later Twentieth Century. He has also taught comic book storytelling at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

There are no superheroes in Asterios Polyp. This is the story of a man who has a high opinion of himself and is not one to concern himself with what others think. He teaches Architecture in Ithaca, New York State, but has never actually built anything (he calls himself a "paper" architect). His life is one of order and straight lines but he marries a woman (Hana, a Japanese-American) quite the opposite: she experiments with objects and form in her art, is emotional and open. When his apartment is lost in a fire he goes on a journey both literal and metaphorical; an attempt to find, and perhaps fix, himself.

This is just a great work of art and I think a master-piece. Story and words aligning perfectly with the beautifully realised stylish pictures that Mazzucchelli is famous for. The art is sometimes experimental but very readable; a spare two colour design, and range of marks and styles. I can't praise this enough: it is a comic-strip work of the highest order but much more than that. People bandy around the term "graphic novel" but I have often been a little uncomfortable with it because so much of the field is, let's face it, still quite childish in many respects (often the story). This is different. A true graphic novel for real grown-ups. Highly recommended.

The Outsider

By Albert Camus

This was Camus' first novel, published in 1942 during the Nazi occupation of France. He was born and raised in French Algeria, to so-called pied-noir parents, but was living in Paris when Germany invaded.

It is a novella so quite short, and it is not hard to read, other than its unsettling protagonist. You are in the head of a very strange young man, Meursault, a strangeness seen clearly from the very first paragraph we read :

Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don't know. I had a telegram from the home: 'Mother passed away. Funeral tomorrow. Yours sincerely.' That doesn't mean anything. It may have been yesterday.

Meursault appears to be quite unemotional and lacks interest in human relationships. An office worker in Algiers, he has a girlfriend and likes to go to the cinema and swim in the sea with her. When she asks if he loves her, he replies "it didn't mean anything and I probably didn't". Not the sort of answer any young woman would expect in the situation. He seems incapable of dissembling at all, or telling the little white lie that side-steps something disagreeable. He probably comes off as inhuman, especially to the lawyer who has to defend him later in the book :

He didn't understand me and he rather held it against me. I wanted to assure him that I was just like everyone else, exactly like everyone else. But it was all really a bit pointless and I couldn't be bothered.

Maybe the French have a word that fits with the above quote: ennui.

Meursault has need of a lawyer because he has killed a man: an Arab. It is unclear why, although there were tensions and intimations of threat. There is no passion in this crime, no anger or blood lust, but the hot sun during the day seems to have left him somewhat unbalanced.

Up until this point, I had not researched the book or its background; what was thought about it, or its place in any philosophical theory. I knew it had some connection with French intellectual thought and existentialism, particularly Sartre. Apparently, Camus rejected the "existentialism" label and preferred "absurdist". I always think it is best to approach a book without too many preconceptions. Today, we might make some diagnosis or other about Meursault's state of mind. There are plenty of those available.

A short, unsettling but worthwhile book. One of the "points" a novel supposedly has is putting the reader into the "head" of the characters and experiencing a different point of view. You certainly get that here.

Fury

By Henry Kuttner

Henry Kuttner died young in 1958, only 42, and so we did not get a chance to see him develop as a writer over a long period. However, given that, he managed to write a lot in his short life, much in collaboration with his wife, Catherine Moore (C L Moore). They would often write together using pseudonyms (e.g. Lewis Padgett). This is my first read of either of them.

In Fury, the human race has fled an uninhabitable Earth for the oceans of Venus, living underwater in cities called "Keeps". The story follows the up and down trajectory of Sam Reed, an angry young man born in a Keep to parents he never knows. Sam is different, and not just because of his extreme ambition and intelligence (his fury) to get ahead. The Keeps have a hierarchy. There is the normal mass of people, happy to stay subdued as long as they are entertained and have a living; and the "Immortals" whose genetics give them a high intelligence and a long life. Sam looks like a base level human, but is he?

Sam Reed is certainly not a very moral or agreeable man and he uses both fair and foul means to rise to the top of the heap, if he can. And if he can stay there. Humanity is stagnating and the Immortals are standing in the way of any reform or progress. They also fight dirty, but so does Sam. Not everyone is happy with a managed life free of adventure or progress, and some want to see some of the excitement of old, perhaps by returning to fight and conquer the inhospitable Venusian land.

This novel is written in a basic "hard-boiled" type of sharp prose reminiscent of a crime thriller, with a clever underdog seeking revenge on the boss. Short and to the point, it is not a masterpiece but a readable pulp science-fiction classic.

Tatja Grimm's World

By Vernor Vinge

I'm quite a fan of Vernor Vinge's work but I've only written once about a novel he wrote: Across Realtime (actually an omnibus of two books). His most famous novels are A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky, both of which I have read twice and loved. He is certainly not a flashy or literary writer, but very capable and full of ideas. He is also not one for the overly gory, explicit or cringe worthy. But he can give you an exciting and gripping story, with surprises. I'm sorry he died last year, so no more new work to enjoy but I still have The Witling to read and a lot of short stories.

Tatja Grimm's World is an early work from Vinge, expanded from a short story published in 1968, then a novel in 1968 and fully formed in 1987. It appears to be almost a fantasy story, with the setting on a world with low technology and little scientific knowledge. Progress is being made however and Vinge does a homage to the "golden" age of SF and the pulps of the 30's and 40's. This world has a big audience for "science-fiction" and "fantasy" type pulp magazines, and some of the publishing houses produce and, literally, ship the magazines to a far flung audience. It's fun reading about the highs and the lows of being a discerning editor on a pulp.

Tatja Grimm herself is a six foot misfit on this world: tall and striking, with a high intelligence and drive for knowledge. Very clever but, it turns out, also quite manipulative and calculating. A good actor as well and her initial saving of the day in a hostage rescue is brilliantly conceived and a lot of fun. There is much more to her than meets the eye then and she has big ambitions that progress as the story unfolds.

I think Tatja Grimm's World is a short, interesting and enjoyable novel from an author just getting going. Vinge is a big believer in the scientific method and its power to push human progress and he continues this theme in his later and better books. This story is an adventure that starts as a rough fantasy but slowly turns into more of a science-fiction tale. It kept my interest throughout and there's a decent ending. A harbinger of good novels to come from the author I think.

And finally, I thought I'd bring up a small bugbear of mine: book covers. To some people (and I'd include my younger and immature self), they can make or break a book.

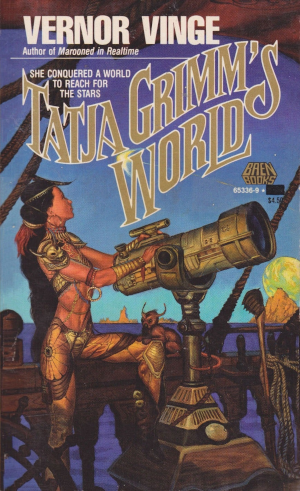

I have the paperback edition with the cover I show above. It's not very good. In fact, it has no relevance I can discern to the story itself. This used to be very common with science-fiction books: a cover that bears absolutely no relationship to the story inside. So, as some sort of compensation, I thought I'd show a different paperback cover for Vinge's novel.

On the right is the cover from Baen Books' 1987 edition, and I think the artist is Tom Kidd (who is new to me). This representation of Tatja Grimm is not too far from her "Barbarian Princess" character in the book. If this intrigues you, then read the book!

Precious Bane

By Mary Webb

I've just re-read Precious Bane, a book I first read back in 2013. It's a very beautiful book. I still haven't tracked down the BBC Radio dramatisation of it that I loved many years ago but the book is hard to beat really.

I don't have much extra to say about the novel except perhaps how it brought to mind Eliot's Adam Bede this time around. Like Eliot's book (which I assume Mary Webb had read), the setting is very rural and farm-based; there is a strong work ethic of the central male character. Both novelists manage to bring the natural world to a colourful and sometimes noisy life, although Webb focuses more on this through Pru Sarn, the "hare-shotten" woman at the heart of it. She has a deep and loving connection to the countryside and the animals in it. I loved the language even though I could not understand the meaning of some of the words used in the Shropshire dialect. Sad, beautiful, moving, tragic and, in the end, uplifting.

War of the Worlds

By H. G. Wells

Wells wrote The War of the Worlds in 1897 and it has become so embedded in our culture that I would expect almost everyone to know the story. How many have read the original though? Most will know it primarily through its film, TV and radio adaptations; a shame because the novel is not only short but a very exciting read.

Some consider Mary Shelley's Frankenstein as the first "science-fiction" novel but to most, Wells' The Time Machine has that honour. At the time, Wells was considered to be writing something called a Scientific Romance but his early books are close to or identical to the modern genre. They really were something new and special.

Under two hundred pages, the book is fast paced and exciting. It introduces many elements and ideas that would go on to have a long life over the course of the Twentieth Century, including technology we can recognise today (even if we are far from its implementation). Technology like : the "black" poison gas the Martians use, the "heat ray" that burns and destroys everything it passes over, a flying machine :

"I believe they've built a flying-machine, and are learning to fly"

I stopped, on hands and knees, for we had come to the bushes.

"Fly!"

"Yes," he said, "fly."

I went on into a little bower, and sat down.

"It is all over for humanity," I said. "If they can do that they will simply go around the world."

He nodded.

What is left for humanity? This book will have shocked and terrorised readers back then as the relentless march of these unstoppable mechanical monsters approaches the capital. Wells does not stint on the horror or shock. I felt the power even today.

And so, from 1897 on into the Twentieth Century, and in a few years the cataclysm for Europe. Europe doesn't need Martians for wholesale destruction with war machines and poison gas. My teenage self would have loved reading this and it would probably instill or fortify a love for books if read at school. A brilliant novel.

The Midwich Cuckoos

By John Wyndham

I remember watching the film Village of the Damned on television when I was quite young and liking it: scary and unsettling. I wish I had read the book it was based on sooner. The film makers did a fairly good job if I recall but the book is better.

Set in a very small English village, Midwich, the whole population has a very mysterious episode where everyone becomes unconscious for a day. A few weeks later, the women discover that they are all pregnant and give birth to "The Children" (the cuckoos of the title). The "Children" (always capitalised in the book) are unusual: precocious, golden eyed and with powerful mind control capabilities. They seem to share a consciousness, the boys separate from the girls. Definitely not human. As they grow and become teens, the full reality and danger of their existence becomes manifest as they protect themselves in a way we cannot fathom or resist.

The villagers take to calling this episode of unconsciousness, the Dayout.

The characters are mostly the sort Wyndham seems to use in his books: middle class and with a common-sense intelligence and capability. The Children are not what they seem but people have a hard time seeing past their appearance. It is a horrifying state of affairs for all, but particularly for the "host mothers", who know the children are not theirs but sometimes have to struggle with their human instincts. Horrifying and unsettling, a situation that is understood clearly by some, particularly an older writer Gordon Zellaby. This might lead to nothing less that the replacement of the human race as masters of the planet.

At heart, a first contact story, it is never actually determined who the Children are or where they come from. This is a book with a great idea and lots of discussion about the ramifications for humanity. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

I have the Penguin edition of Selected Essays, Poems and Other Writings of George Eliot. So far unread but I did have a look at the introduction because it is by A. S. Byatt, an author I have a lot of time for. Byatt's novel Possession is one of my favourite books. Back in 2013 when I read it, I had not read any Eliot and was unaware of the debt owed to the writer of Middlemarch.

Byatt's introduction starts by quoting the letter William Hale White sent to the Athenaeum magazine in 1885. White was responding to John Walter Cross's Life of Eliot, who had died in 1880. She married Cross quite late in life and he was 21 years her junior. White was not impressed with Cross's work and his letter is a great summary of what made Eliot great.

From the Introduction, and quoting White's letter :

As I had the honour of living in the same house, 142, Strand, with George Eliot for about two years, between 1851 and

1854, I may perhaps be allowed to correct an impression which Mr Cross's book may possibly produce on its readers.

To put it very briefly, I think he has made her too 'respectable'. She was really one of the most sceptical, unusual

creatures I ever knew, and it was this side of her character which was to me the most attractive. She told me that it was

worthwhile to undertake all the labour of learning French if it resulted in nothing more than reading one book -

Rousseau's Confessions. That saying was perfectly symbolical of her, and reveals more completely what she was, at any rate

in 1851-4, than page after page of attempt on my part of critical analysis. I can see her now, with her hair over her

shoulders, the easy chair half sideways to the fire, her feet over the arms, and a proof in her hands, in that dark

room at the back of No. 142, and I confess I hardly recognise her in the pages of Mr Cross's - on many accounts - most

interesting volumes. I do hope that in some future edition, or in some future work, the salt and spice will be

restored to the records of George Eliot's entirely unconventional life. As the matter now stands she has not had full justice

done to her, and she has been removed from the class - the great and noble church, if I may so call it - of the Insurgents,

to one more genteel, but certainly not so interesting.

Not genteel, but insurgent.

The Celts

By Nora Chadwick

I'm interested in Iron Age and "Dark Age" history, especially British, and this means the Celts in particular. It's frustrating however because of the sparse source material. I read Ian Stewart's The Celts a few weeks ago and this rekindled an interest in reading a bit more; with this in mind, I picked up Nora Chadwick's The Celts second-hand.

Chadwick's book is quite different to Stewart's. His is fairly heavy going, with a lot of information in it and quite densely packed. More importantly, it is a "modern" history: that is, how, and by who, the "Celts" were (re)discovered and researched after the Renaissance. It contains little ancient history. It is a detailed, good overview of this modern history.

In contrast, Chadwick's The Celts was published in 1970 and is much more concise. Although it might be a little out of date in places, it is a well written and useful introduction to the ancient history of the Celts: their origins and movement through Europe, the language and culture, social conditions and religion, and also art and literature. It covers a period from the first millenium BC to medieval times. I enjoyed reading this book much more, even though it could be a little repetitive in places, especially when discussing Celtic Art. Art, literature and myth came last in the book, with a greater concentration on the Irish side, of which more writing has been preserved.

I thought the last chapter about literature was well done. She summarised the stories in a few paragraphs and related them to each other (and those of other nations e.g. Irish and Welsh). On the page, myth and folklore can sometimes be a slightly repetitive read, losing the liveliness of an oral or pictorial recitation, but she managed to describe them in an interesting way. I saw some criticism of this book (Amazon I think) regarding it as "by a scholar for scholars". I would disagree about that: for anyone with an interest and a little experience reading a popular history book, this is still a fine introduction. On that score, it is better than Stewart's book.

I've now picked up John Collis's The Celts. I read it a few years ago but am now flicking through it once again.

The Final Solution

By Michael Chabon

I loved Chabon's Yiddish Policeman's Union and have bought a few of his other books on the back of that. This very slim book is one of them.

First published in The Paris Review, it is a "murder mystery" with an old man (we never learn his name) helping a police detective solve a murder and the kidnap of a parrot. Taking place during the Second World War in the south of England, the parrot is a special companion to a German boy, assumed to be Jewish and in England as part of the Kindertransport. This is not clarified however. Neither is the parrot's habit of speaking long strings of numbers e.g. zwei eins sieben fünf vier sieben drei.

I picked this up to read partly because it was so slight, so not a huge investment in time. Like the last book of his I read, it is well written and has a wry humour throughout. The old man is a particularly irascible and funny character. Much is left unsaid regarding the boy's history, or the "numbers" the Parrot is repeating, as well as the "train song" it sometimes sings. This is not as good as the Yiddish Policeman, it seemed a little "light", perhaps too "lightweight". However, still an enjoyable enough read. I am glad I picked up his Yiddish Policeman's Union novel first because I know how good he can be. He won the Pulitzer Prize for The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay; I am looking forward to reading that.

The Celts

By Ian Stewart

I saw a positive review of this book and I'm interested in iron age history in Britain (including the Celts) so bought it. It was worth reading but not quite what I expected.

It's a dense book and Stewart (an academic at the University of Edinburgh) has done an amazing job researching and describing the "modern" history of the Celts: "modern" history starts with the renewed interest they were shown from the Renaissance onwards, and the history is slowly elucidated through the people doing the (metaphorical) digging. It was back then that some started to consider who the earlier, pre-Roman, peoples of Europe really were and the old "origin" myths began to seem increasingly problematic. Having said that, the biblical fantasy about descent from Noah's grandson Gomer persisted for centuries.

What this history does not do is cover much in the way of archaeology, artifacts or genetics. On occasion we get something dug up or old monument looked at, but the book is mainly a history of the many individual researchers and historians, clubs, societies and (increasingly) academics, and their (often slow) search for the truth. This does complement many of my other books in this field.

There are some people we meet here that deserve some more recognition, including J.C. Prichard, an Anglo-Welsh ethnologist and philologist, who made some crucial advances in the 19th Century identifying where the Celtic languages came from. In particular, the fact that they were descended from the ancient Indo-European family (like German, Latin, Greek and even Sanskrit). Much of the science in the book is the science of Philology, where a language is studied and its branching off from other languages, as well as evolution over time, is investigated. Another man worthy of more note is Johan Kaspar Zeuss, a Bavarian scholar, who toiled to shed light on the origin and history of Europe's languages, eventually producing a major work Grammatica Celtica. He proved the Indo-European origin of the Celtic languages and also the mechanism of their split to the various different forms we know and that exist today (e.g. Old Irish/Irish Gaelic, Breton, Welsh etc.). All of the work he did was on the continent using sources of Old Irish hidden away in monasteries for hundreds of years. Finally, it was seen that, although it was a sibling language to Celtic on the Indo-European tree, German was not itself Celtic. This sort of question has confused matters since Caesar himself.

An interesting book that covers the huge French and (particularly) German contribution, as well as the major (and minor) work done in Wales, Scotland, Ireland and England. In the end, however much has been discovered about the ancient Celts, the core element of their presence, today and in the past, is the language. Although much diminished, they are still living languages. This book was hard work sometimes because it is quite slow and detailed, so it will not be for everyone (although that's not it's aim). It will be a worthwhile read for those that want to know how the history has been worked out over the past few centuries however.